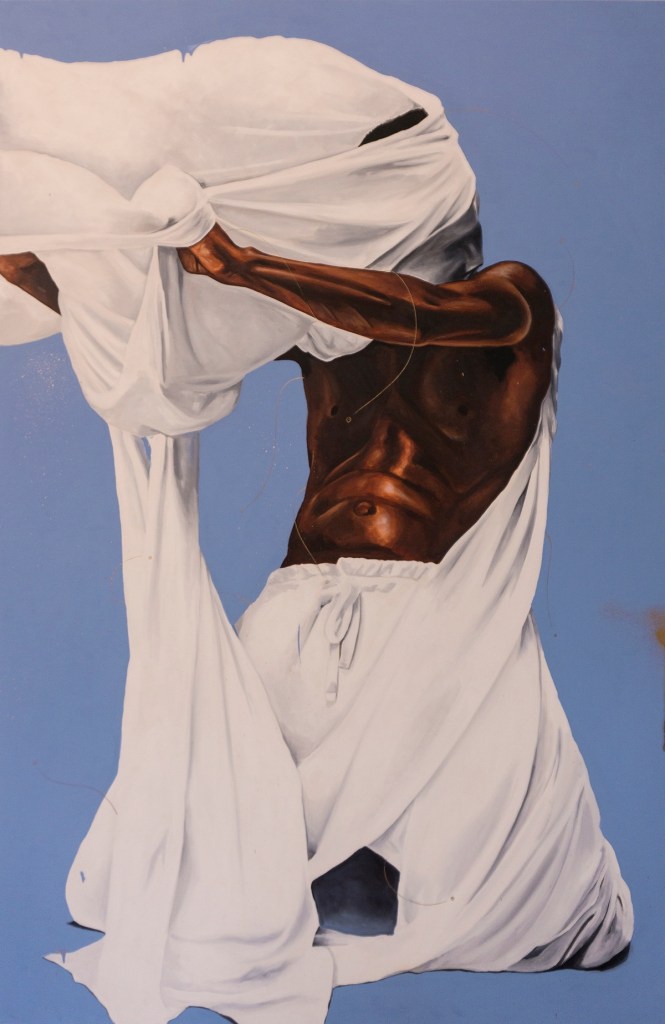

Photograph by Stefano de Luigi

Here goes another martyr, †Alexey Navalny died in Russian’s prison.

Breathtaking portrait of Navalny from 2011 :

Navalny and his supporters are keenly aware of such brutal reprisals. “I have a lot of respect for what he’s doing, but I think they’ll arrest him,” I was told by a high-ranking employee at a state corporation that Navalny is investigating. “He’s taunting really big people and he’s doing it in an open way and showing them that he’s not afraid. In this country, people like that get crushed.” When I asked Navalny’s mother, Lyudmila, if she was afraid for her son, she melted into tears before I even got the question out. “I have forgotten what normal sleep is,” she said. “I believe in what he’s doing, he’s doing the right thing, but I’m not ready. I’m not ready for my son to become a martyr.”