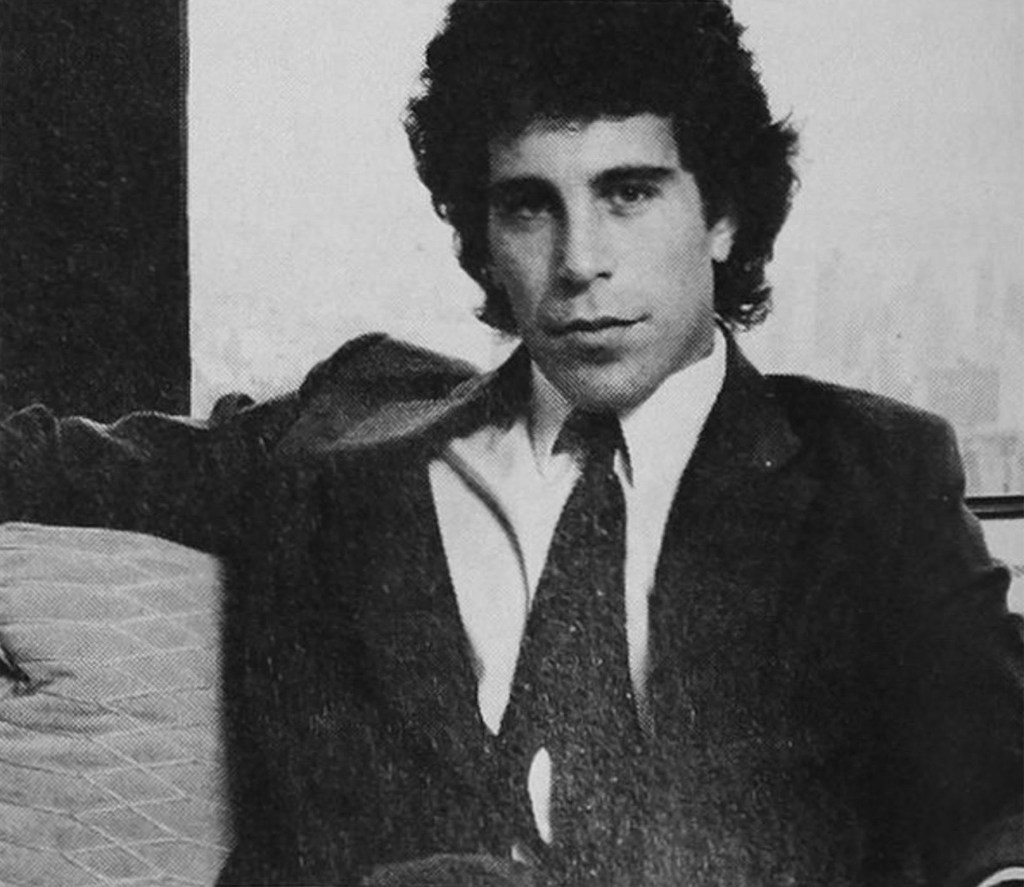

“Why did you do it?” Tennenbaum stammered.

Without an impressive degree or two, Epstein said, “I knew nobody would give me a chance.”

This resonated with Tennenbaum. He had benefited from his own share of second chances over the years. And so he agreed to give Epstein one as well.

It was perhaps the first example of Epstein getting caught cheating — and then avoiding punishment thanks to his uncanny ability to take advantage of those in positions of power. This would become a lifelong pattern, one that largely explains Epstein’s remarkable success at amassing wealth and, eventually, orchestrating a vast sex-trafficking operation.